Developing Brain Power

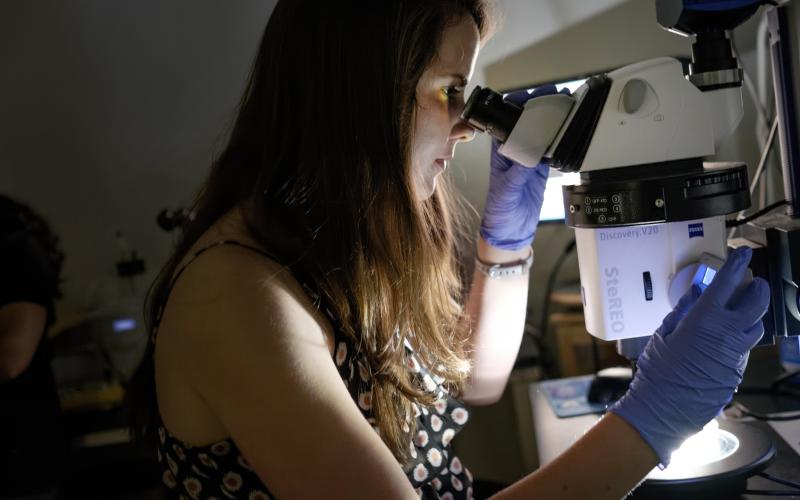

Sarah Cottrell-Cumber has always been fascinated with space. In high school she worked in a summer scholar program at NASA. She came to the University of Virginia as a physics major and planned to be a space scientist — with the universe as her laboratory — until she discovered the universe within.

“I took one course: introduction to neurobiology, “ she says, “and it changed everything.”

Leaving physics behind, Cottrell-Cumber switched majors and signed up for one of U.Va.’s many neuroscience laboratories. Her present research is looking for novel mechanisms for treating multiple sclerosis patients by repurposing current drugs as a combination therapy.

“I still enjoy being in the lab whenever I can. It’s my happy place.”

The undergraduate neuroscience program is dedicated to finding such happy places for a small number of promising students, and the opportunity may not happen a moment too soon. Developing gifted researchers in neuroscience has never been more important. Brain research lies at the center of many pressing topics of public health, wellness, health care and quality-of-life issues.

“There are a lot of problems where the brain is the culprit,” says Dr. Alev Erisir, professor in the department of psychology and director of the neuroscience program. “

The brain health of the aging population remains a major issue, she says, but ongoing neuroscience research could also have an impact on such challenges as autism, Parkinson’s, attention deficit disorder and multiple sclerosis. And the importance of neuroscience even extends beyond health concerns.

“The brain controls everything we are as human,” explains Dr. Sarah Kucenas, assistant professor of biology, who runs a neuroscience research lab on grounds. “The nervous system allows us to interact with the environment. That’s how we love. That’s how we speak. That’s how we pass traditions on. It’s all governed by our nervous system.”

By its very nature, neuroscience crosses disciplines. Functioning under the auspices of the College of Arts and Sciences, U.Va.'s program is also interdisciplinary — offering its courses through the departments of psychology and biology, with research labs functioning through those schools as well as the school of medicine.

While U.Va. offers exceptional experiences for undergraduates in a number of disciplines, the neuroscience program differs from most in two ways. First, the program incorporates third- and fourth-year students rather than simply fourth-years. Second, the program emphasizes laboratory experience, not only during the student’s time in the program but also beforehand.

“All of our applicants have been in the research labs for at least a semester,“ Erisir explains. “We want to see the student get in the lab and smell the air a little bit.”

Dr. David Hill, currently chair of the department of psychology, founded the neuroscience undergraduate program in 2003 and directed the program for its first three years. He estimates there are nearly 70 research labs on grounds. The labs promote interaction at many academic levels, ranging from faculty to graduate students to undergraduates — a rich environment for learning and for research. Program size is another key factor to the program’s success. Hill says the program was designed to be a “boutique major,” limited to just 25 new students per year.

The capstone course of the program is a weekly seminar attended by undergraduate and graduate neuroscience students, as well as faculty and post-doctoral researchers. The speaker for the week might be a U.Va. medical school faculty member or a distinguished international neuroscientist. After the formal presentation, undergraduates are given a 45-minute session with the speaker.

“I was able to sell it as a recruiting opportunity for the seminar speakers,” Hill recalls, “because they had a captive audience of really bright students they could try to attract to their graduate programs. But it also gave these young undergraduates access to people most faculty members would not get.”

“During the seminar class, we have a time to ask questions all by ourselves as undergraduates,” says Kate Kingsbury, a rising fourth-year whose research investigates a class of ganglion cells in the retina. “

The deep investment in lab work and faculty interaction sets U.Va.’s program apart from other schools. The Society for Neuroscience maintains a directory of university neuroscience programs. Of 32 undergraduate programs listed on the society’s website, at only two schools does the training faculty outnumber the students enrolled: U.Va. and the University of Arizona. That kind of high-contact interaction would be unavailable in a larger program.

The emphasis appears to have paid off.

“People recognize that undergraduates at the University of Virginia are above most other universities in terms of their contribution to the science going on,” Dr. Sarah Kucenas says. In fact, the first journal article published out of her lab was produced by an undergraduate, appearing in The Journal of Neuroscience in 2013.

“The community thought it was fantastic work,” she says. “People are often astonished when they find out that these students are 20, 21 years old. They are not 35-year-old post-docs. They’re really still babies when you consider the scientific training.”

Students participate fully in the laboratory, often helping graduate students with ongoing research projects when not conducting their own independent research. Typically, about half of the graduates of the program go on to medical school, Erisir says, while others go to Ph.D. programs and some to pursue combined M.D./Ph.D. degrees.

For Jennifer Sokolowski, the program was integral in helping her decide to stay on at U.Va. to pursue the rigorous combined degree. During her undergraduate years, she completed a study tracing the anatomy of the olfactory system, which was published in The Journal of Comparative Neurology after she graduated in 2007.

“Being exposed to hands-on research in a serious way made me realize that I have a stamina to do an M.D./Ph.D.,” say Sokolowski, who looks forward to completing the sequence in 2015. “In lab work, the highs are not as common as the lows. But when you have an experiment that works, you can ride that for a while.”

“Very frequently, science surprises you,” Cottrell-Cumber says. “It’s not just knowledge that you find in a textbook; it’s about finding things firsthand in the lab. There is a lot of trial and error.”

“Research is hard. It is not immediately rewarding,” Erisir admits. “But there are incredible rewards that come from a life of research. Most of us consider science to be not a job but a lifestyle.”

Scientific research seems to proceed at a dizzying pace, often leading to public misconceptions about the nature of the work.

“They don’t know about all the late nights, all the really long days where I just wanted to quit,” Cottrell-Cumber adds. “But it makes it all work worthwhile when you get to present your work and you realize that it may help other people.”

Of 14 neuroscience graduates this past year, eight had papers published and more than 10 were awarded research fellowships — funded through a number of resources within the university.

“They are completely equipped for graduate school,” Erisir says. “We are so proud of them.”

For many good reasons, neuroscience is trendy — vast, complex, inviting new breakthroughs. Yet it is also deeply fundamental, in that all science is brain science. Every discovery is a brain discovery, along with every line of poetry, every memory, every well-structured argument.

There may still be a universe to study, but every fresh insight in every field comes to us by way of the universe within.